A Testament to the Endurance of Love

As featured on NPR, The New York Times, The Rumpus, Kveller, Psychology Today, and Times of Israel

“An intimate, intuitive, emotionally vivid family account that finds hope in reconciliation.”

Motina Books presents

WHEN SHE COMES BACK

A Memoir

RONIT PLANK

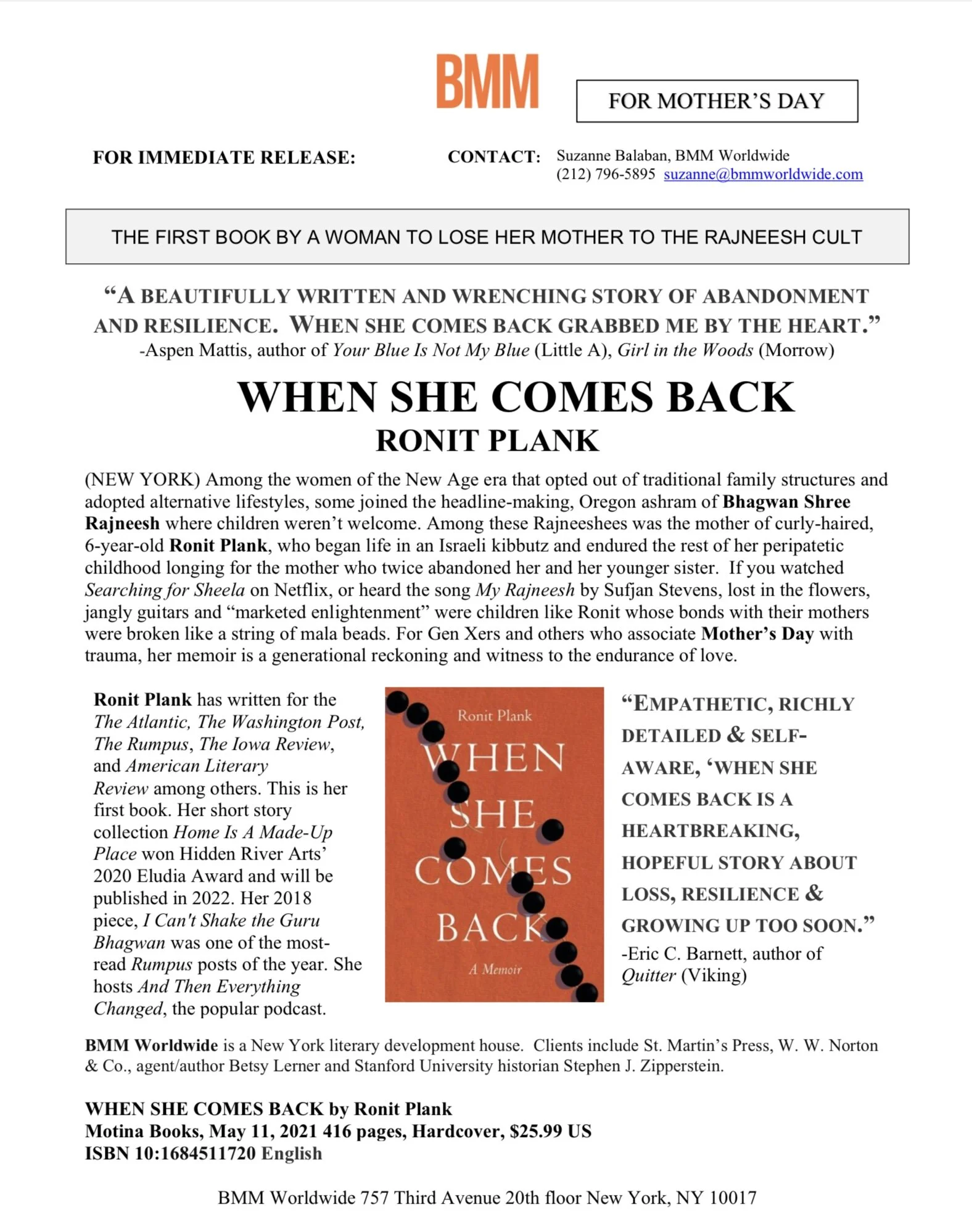

“A beautifully written and wrenching story of abandonment and resilience. ‘When she Comes Back’ grabbed me by the Heart.”

“Empathic, richly detailed and self-aware, ‘When She Comes Back’ is a heartbreaking, hopeful story about loss, resilience and growing up too soon.”

“In this fascinating coming-of-age memoir, Ronit Plank poignantly explores the resilience of a child longing for her mother and ultimately leads us along her path to reconciliation. When She Comes Back is a stunning debut.”

Present at the first glimmer of woke, when hippies began seeking alternatives to the nuclear families, religions, and systemic maladies of “Amerika”, were those who joined the Oregon ashram of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh where children were unwelcome.

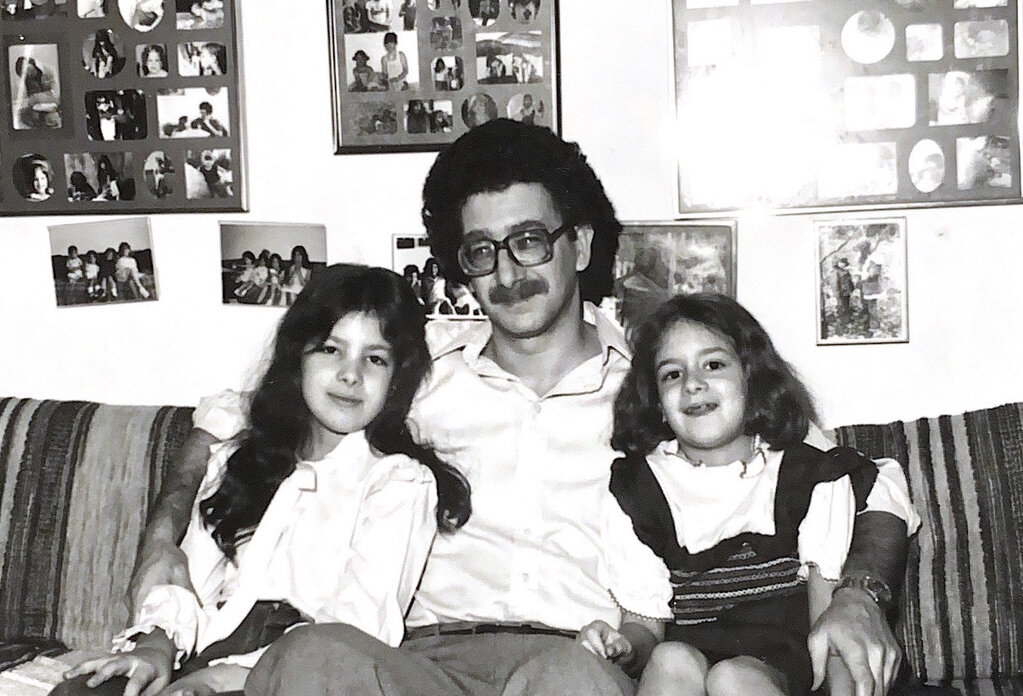

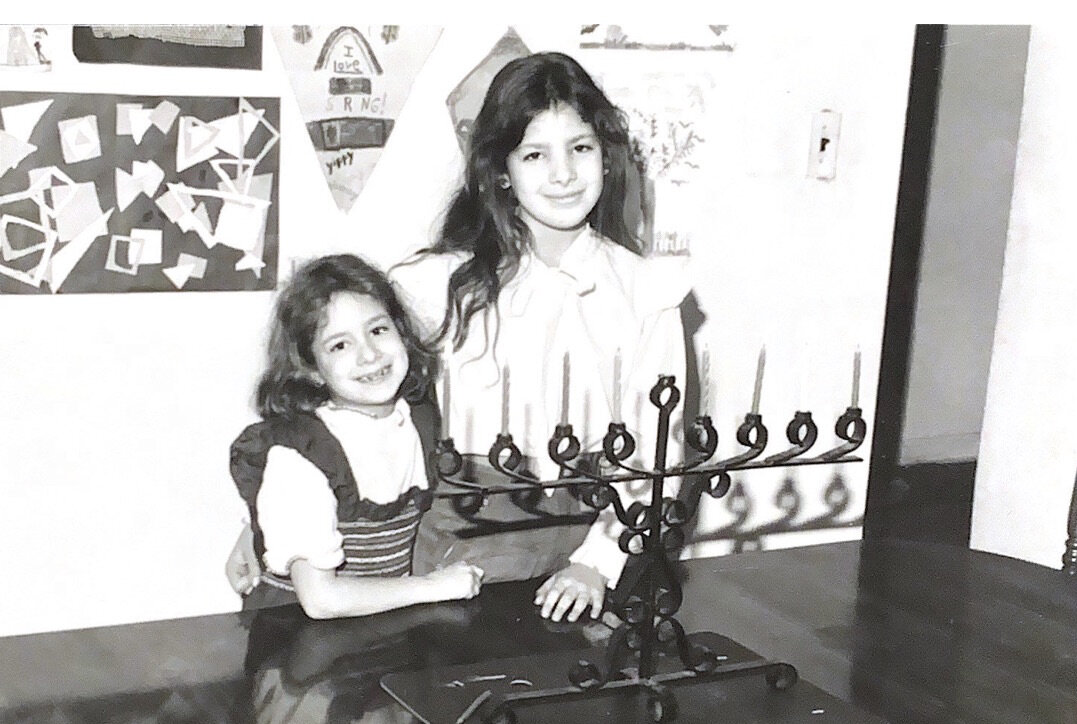

One of those Rajneeshees was the mother of 6-year old Ronit Plank, an adorable, forthright little girl who began life in a kibbutz & grew up in Seattle, Newark & Queens pining for the mother who twice abandoned her & her sister to follow Rajneesh.

If watching Wild Wild Country on Netflix, or listening to My Rajneesh by Sufjan Stevens makes you yearn for the countercultural 70’s and early 80’s, remember that lost in the flowers, jangly guitars and marketed enlightenment were silent victims like Ronit whose vital bonds with their mothers were snapped like a string of mala beads.

For anyone whose mother sacrificed them on the altar of social progress, or is having second thoughts about their own parenting choices, WHEN SHE COMES BACK is an urgent warning, intergenerational reckoning, and witness to the endurance of love.

〰️ About the Author 〰️

Ronit Plank has written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Rumpus, The Iowa Review, and American Literary Review among others. This is her first book. Her short story collection Home Is A Made-Up Place won Hidden River Arts’ 2020 Eludia Award and will be published in 2022. Ronit also hosts the popular podcast And Then Everything Changed to highlight the lives of people who have survived hardship, trauma or pain and have made it their mission to help others find their way. Ronit Plank's 2018 piece, I Can't Shake the Guru Bhagwan was one of the most-read Rumpus posts of the year.

〰️ Book Excerpt 〰️

from chapter TWO

“What struck me when we went to these meditations was the adults’ unusual behavior towards children. They didn’t make more than hazy eye contact with us; there wasn’t any sense of curiosity that two little ones had arrived, the only kids in the place. No impulse at all to settle us in or help make us feel welcome. Even though people in Seattle seemed pretty reserved—make that really reserved—grownups usually tried to be friendly toward us. The way these men and women looked around us, through us, troubled me. I couldn’t verbalize my worry then, but it nagged at me that my mother didn’t seem to notice that the people she wanted to spend more time with basically ignored her children.

I was already becoming more insecure in my attachment to her but I still knew from my first four years of life on a kibbutz in Israel that grown-ups were supposed to guide children and treat them with gentleness. I would later learn that Bhagwan felt children were a distraction, that they made spiritual growth difficult to attain. In fact, he encouraged sterilization and vasectomies for sannyasins on his ashram, and later on his ranch in Antelope, Oregon. Decades later my mother told me herself that “Bhagwan taught that children were obstacles to enlightenment.”

〰️ OFFICIAL PlaylisT 〰️

Music from a coming-of-age memoir about giving up one's power, growing up too fast, and what happens when the person your world revolves around can't stay.

〰️ Social TRAILER 〰️

“About two hundred people lived on the kibbutz. Some younger, unattached women and men passed through to volunteer for several months or a year, but most of the kibbutzniks were married couples with children. Each married couple had their own one-bedroom, one-bathroom bungalow with a kitchenette, but every other aspect of life was shared and decisions on the kibbutz were made as a group.”